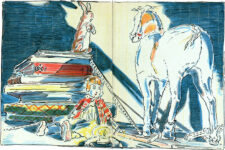

Men stood by their fences and looked at the ruined corn, drying fast now, only a little green showing through the film of dust. The men were silent and they did not move often. And the women came out of the houses to stand beside their men—to feel whether this time the men would break. The women studied the men’s faces secretly, for the corn could go, as long as something else remained. The children stood near by, drawing figures in the dust with bare toes, and the children sent exploring senses out to see whether men and women would break. The children peeked at the faces of the men and women, and then drew careful lines in the dust with their toes.

Horses came to the watering troughs and nuzzled the water to clear the surface dust. After a while the faces of the watching men lost their bemused perplexity and became hard and angry and resistant. Then the women knew that they were safe and that there was no break. Then they asked, What’ll we do? And the men replied, I don’t know. But it was all right. The women knew it was all right, and the watching children knew it was all right. Women and children knew deep in themselves that no misfortune was too great to bear if their men were whole. The women went into the houses to their work, and the children began to play, but cautiously at first. As the day went forward the sun became less red. It flared down on the dust-blanketed land. The men sat in the doorways of their houses; their hands were busy with sticks and little rocks. The men sat still—thinking—figuring.

― The Grapes of Wrath, Jon Steinbeck

This quote is from John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath,” a novel set during the Great Depression, focusing on the economic hardship and social injustices faced by migrant workers and poor farmers.

Steinbeck’s work is renowned for its vivid portrayal of the struggles of the working class, and this passage is a powerful example of his ability to capture the human spirit amidst adversity.

The scene described here highlights the aftermath of a dust storm that has ruined the corn crop, a disaster for the farming families dependent on this crop for their livelihood.

The detailed observation of men standing silently by their fences, women coming out to gauge their men’s resilience, and children tracing figures in the dust with their toes, all contribute to a poignant picture of a community facing the brink of despair.

Steinbeck uses this scenario to explore themes of resilience, family unity, and gender roles within this community.

The men’s silence and stillness reflect their shock and uncertainty about the future, a natural response to seeing their hard work and hopes destroyed.

The women’s actions, coming out to stand beside their men, show their role as emotional anchors within the family.

Their concern is not just for the lost crop but for the emotional and psychological state of their men; the corn “could go, as long as something else remained.” This “something else” suggests the strength of spirit, hope, or the will to persevere.

Children, in their innocence, look to the adults for cues on how to respond to the crisis, their actions reflecting a mix of curiosity and apprehension.

The arrival of horses, seeking water at the troughs, adds another layer to the scene, emphasizing the natural continuation of life and the need to address immediate concerns despite the disaster.

As the passage progresses, the shift in the men’s demeanor from perplexity to anger and resistance signifies a turning point.

This change reassures the women and children that despite the dire circumstances, the core of their community – the resilience and determination of its people – remains intact.

The women returning to their work and the children resuming their play, albeit cautiously, symbolize a return to normalcy and the enduring human capacity to adapt and continue in the face of hardship.

Steinbeck’s narrative here is more than just a depiction of a moment of crisis; it’s an exploration of the dynamics within a community and family units when faced with existential threats.

It speaks to the idea that the strength of a community lies not in its material possessions but in its people’s ability to stand together, support one another, and face adversity without breaking.

This resilience, shared by men, women, and children alike, forms the backbone of their identity and hope for the future, a theme that resonates throughout “The Grapes of Wrath.”