Gustav Klimt (1862-1918): Death and Life, 1910, reworked in 1915, oil on canvas, Leopold Museum, Vienna

Gustav Klimt’s large painting ‘Death and Life’, created in 1910, features not a personal death but rather merely an allegorical Grim Reaper who gazes at “life” with a malicious grin.

This “life” is comprised of all generations: every age group is represented, from the baby to the grandmother, in this depiction of the never-ending circle of life.

Death may be able to swipe individuals from life, but life itself, humanity as a whole, will always elude his grasp. The circle of life likewise repeats itself in the diverse, wonderful, pastel-coloured circular ornaments which adorn life like a garland.

Gustav Klimt described this painting, which was honoured with a first prize at the 1911 International Art Exhibition in Rome, as his most important figurative work. Even so, he seems to suddenly no longer have been satisfied with this version in 1915, for he then began making changes to the painting—which had been framed for long by that time.

The background, reportedly once gold-coloured, was made grey, and both death and life were given further ornaments. Standing before the original and examining the left interior edge of Josef Hoffmann’s frame for the painting, one can still discern traces of the subsequent over-painting, which was done by Klimt himself.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 – 1669): The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp, 1632, oil on canvas

Rembrandt was only twenty-five when he was asked to paint the portraits of the Amsterdam surgeons. The portrait was commissioned for the anatomy lesson given by Dr Nicolaes Tulp in January 1632.

This is a more complicated composition than it at first appears. Understandably, the focal point of the image is Dr. Tulp, the doctor who is shown displaying the flexors of the cadaver’s left arm. Rembrandt notes the doctor’s significance by showing him as the only person who wears a hat. Seven colleagues surround Dr. Tulp, and they look in a variety of directions—some gaze at the cadaver, some stare at the lecturer, and some peek directly at the viewer. Each face displays a facial expression that is deeply personal and psychological.

In this group portrait, the young painter displayed his legendary technique and his great talent for painting lifelike portraits.

The compositionally innovative, and deeply psychological painting launched Rembrandt to fame and wealth and influenced generations of artists to come.

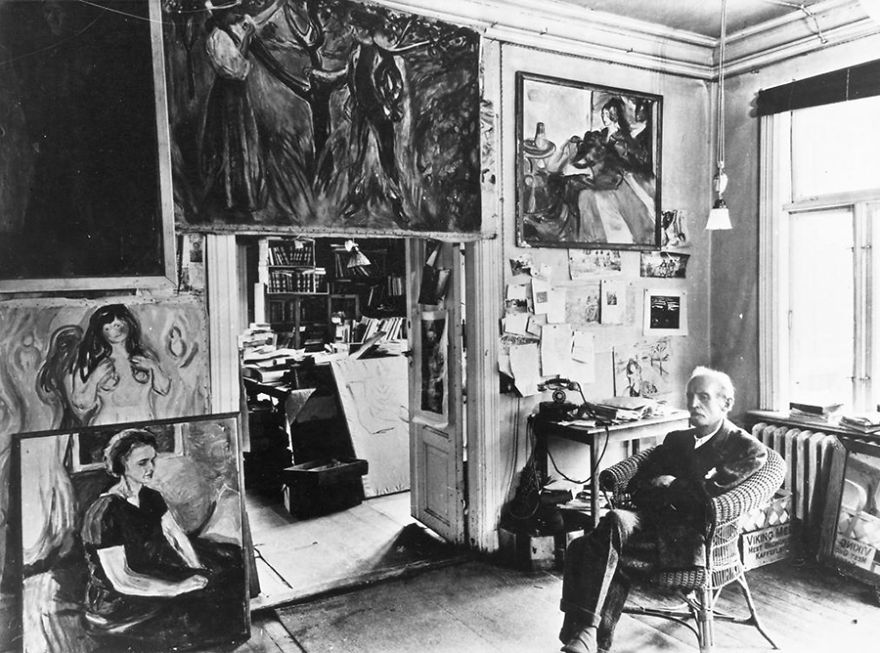

Emile Foubert (1848 – 1911): The Artist Dreaming in His Workshop, 1886, oil on canvas

Emile Louis Foubert was a French history painter. His painting depicts a self-portrait of the artist in his studio, where he dreams away.

We can distinguish the muses, objects of his imagination, transparently in gray-blue shades on the wall among the paintings of Millet’s and Corot’s and the death mask of Géricault hung high up on the wall, as tribute to these masters of 19th-century painting.

Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009): Christina’s World, 1948, tempera on panel

American artist, Andrew Wyeth remained loyal to Realism throughout his career and perfected this style through countless paintings depicting rural settings.

The woman in the painting is Christina Olsen (1893 – 1968), a neighbor of Wyeth’s in South Cushing, Maine, one of the two locations where he made all of his paintings, the other being his home in Chadds Ford, PA.

Wyeth’s inspiration for this powerful image came about when he saw Christina crawling outside in the grass from his window. She had lost the use of her legs in her early 30’s due to a degenerative muscular condition. She refused to use a wheelchair, preferring to crawl, as depicted here, using her arms to drag her lower body along. “The challenge to me,” Wyeth explained, “was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless.”

The high level of detail Wyeth gave to every object in his paintings encourages intense inspection, but his titles reveal the inner significance of their outwardly straightforward subjects. The title Christina’s World, courtesy of Wyeth’s wife, indicates that the painting is more a psychological landscape than a portrait, a portrayal of a state of mind rather than a place.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919): Bal du Moulin de la Galette (Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette), 1876, Oil on canvas

‘Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette’ is undoubtedly Renoir’s most important work of the mid 1870’s. It was shown at the Impressionist exhibition in 1877.

The painting depicts a typical Sunday afternoon at the original Moulin de la Galette in the district of Montmartre in Paris. In the late 19th century, working class Parisians would dress up and spend time there dancing, drinking, and eating galettes into the evening.

Though some of his friends appear in the picture, Renoir’s main aim was to convey the vivacious and joyful atmosphere of this popular dance garden.

The study of the moving crowd, bathed in natural and artificial light, is handled using vibrant, brightly coloured brushstrokes. The somewhat blurred impression of the scene prompted negative reactions from contemporary critics.

This portrayal of popular Parisian life, with its innovative style and imposing format, a sign of Renoir’s artistic ambition, is one of the masterpieces of early Impressionism.

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828): Saturn Devouring One of his Children, 1819-23, Plaster mounted on canvas

Saturn Devouring One of his Children’ is perhaps the cruellest of the Black Paintings, or ‘Pinturas Negras’, which are a series of fourteen works painted at the artist’s his villa outside Madrid between 1819 and 1823.

The work depicts the Roman god Saturn, also Titan Kronos in Greek mythology, savagely eating one of his children. The imposing figure of Saturn emerges from the darkness with mad-like eyes bulging from his face as he prepares to take a bite as his fingers dig into his child.

The corpse is motionless and lifeless, his head and arm have been already been consumed. Only the flesh and blood of the mutilated corpse have colour in the darkened scene, which represents Saturn’s fear of being usurped by one of his children.

The nightmare quality in the work is combined with myth to make an epochal statement: this is the madness of truth. W

hether this is a reflection of Goya’s own mental state, or an allegory on the situation in a country that was consuming its own children in bloody wars and revolutions, or a statement on the human condition generally, may remain open.

It could also be a reflection of the situation of the enlightened man who has lost his God and is able to experience only mercilessness on cosmic scale.

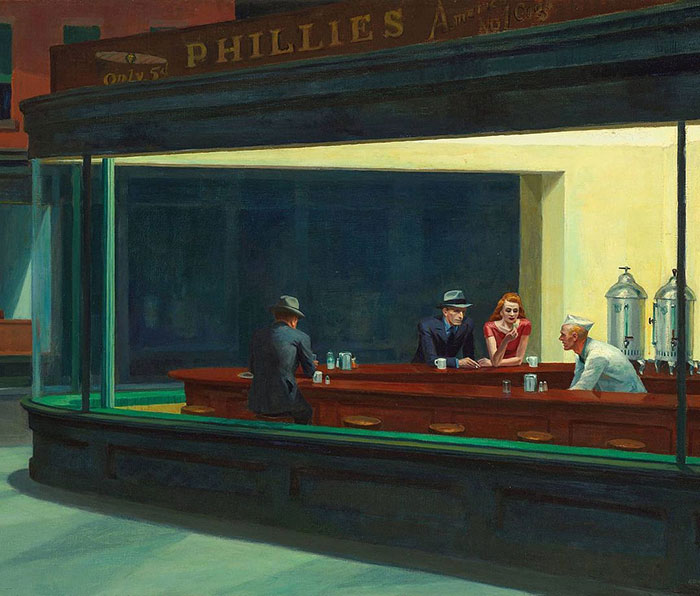

Edward Hopper (1882–1967): Nighthawks, 1942, Oil on canvas

The best-known of Edward Hopper’s paintings, ‘Nighthawks’ shows customers sitting at the counter of an all-night diner.

Hopper said that Nighthawks was inspired by “a restaurant on New York’s Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet, but the image—with its carefully constructed composition and lack of narrative—has a timeless, universal quality that transcends its particular locale.

The viewpoint is cinematic—from the sidewalk, as if the viewer were approaching the restaurant. The diner’s harsh electric light sets it apart from the dark night outside, enhancing the mood and subtle emotion.

Hopper’s understanding of the expressive possibilities of light playing on simplified shapes gives the painting its beauty. Hopper eliminates any reference to an entrance, and the viewer, drawn to the light, is shut out from the scene by a seamless wedge of glass.

The four anonymous and uncommunicative night owls seem as separate and remote from the viewer as they are from one another. (The red-haired woman was actually modeled by the artist’s wife)

In place of meaningful interactions, the four characters are involved in a series of near misses in Hopper’s painting. The man and woman might be touching hands, but they aren’t. The waiter and smoking-man might be conversing, but they’re not.

And then we realize that Hopper has placed us, the viewer, on the city street, with no door to enter the diner, and yet in a position to evaluate each of the people inside. We see the row of empty counter stools nearest us. We notice that no one is making eye contact with any one else. Up close, the waiter’s face appears to have an expression of horror or pain. And then there is a chilling revelation: each of us is completely alone in the world.

Hopper denied that he purposefully infused this or any other of his paintings with symbols of human isolation and urban emptiness, but he acknowledged that in Nighthawks “unconsciously”, probably, he had painted the loneliness of a large city.

Prisoners Exercising (1890) by Vincent van Gogh.

In 1888, Van Gogh, who was suffering from severe bouts of depression, cut his own ear off after getting in a fight with fellow artist Paul Gauguin. He then gave it to a prostitute named Rachel as a token of his affection. Others have stipulated that it might have been Gaugin who had cut off his ear during the scuffle, knowing that no one would believe the mad artist.

A few months after the incident, Van Gogh voluntarily committed himself to an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. It was during this time that he wrote, “Sometimes moods of indescribable anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time and fatality of circumstances seemed to be torn apart for an instant.”

Since the asylum limited him to the outside world, Van Gogh began to paint copies of works made by other artists. One of those works of Newgate prison yard in London (swipe left) by French artist Gustave Doré.

The painting shows a group of prisoners walking in circles around a small prison yard that is surrounded by brick walls. The prisoners walk past the guards so they would remember their faces. It has been suggested that the face of the prisoner in the center of the painting looking outward is Van Gogh himself.

Van Gogh shot himself just a few months after completing the painting.

Charles Hermans (1839–1924): Bal Masqué, 1880, oil on canvas

When exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1880, the Brussels born and trained Charles Hermans’ view of a Bal Masqué combined a recognizable venue, the luxurious theater of an opera house, with an even more distinct social event, the masked balls that enlivened the winter season. \

The extravagant masked costume balls that were held throughout Paris, Brussels and other European cities during the six weeks before Ash Wednesday and the Lenten restriction were among the most talked about spectacles of the late nineteenth century.

From midnight until five o’clock in the morning, and for the price of a ticket, daring young women could mix with men of aristocratic, financial, and political prominence who flocked to the events. At the opera house, the audience pit was cleared for dancing and the opera orchestra itself provided music for waltzes or mazurkas and even the controversial can-can.

Women dressed as glamorized stevedores, shepherdesses, or in any other costume that revealed more of their figures than street dress permitted, and they danced with abandon – their reputations protected by small black domino masks that gave the illusion of anonymity.

Men, most frequently dressed in traditional evening clothes, might dance, but mostly they watched and hoped to arrange a post-ball rendezvous.

Ilya Repin (1844-1930): Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16, 1581, 1885, oil on canvas

In 1885 Ilya Repin completed one of his most psychologically intense paintings based on the story of Ivan the Terrible killing his son.

This canvas displays a horrified Ivan embracing his dying son, whom he had just struck and mortally wounded in an uncontrolled fit of rage.

The psychological contrast of the main characters in the painting achieves unusual tension. We see the nearly icon-like, calm face of the tsarevich and the face of Tsar Ivan, with its bulging eyes and covered in drops of blood. The red colour dominates in the painting. It is everywhere – from the rose colour of the tsarevich’s shirt to the dull Bordeaux of the background. The painterly expression of the picture was extraordinary for its time.

Repin dedicated this painting to Tsar Alexander II who was assassinated in 1881 by a group associated with the reform movement.

With this painting, Repin warned, “Be careful what you do with your rage, you could end up doing more harm than good.” The assassination caused a great setback for reform in Russia.

Alexander II had completed plans for an elected parliament the day before he died, but had not yet released the plan to the Russian people. Had he lived another forty-eight hours, which was the day the plan was to be released, Russia might have followed a path to constitutional monarchy instead of the long road of oppression that defined his successor’s reign. The first action Alexander III took after his coronation was to tear up those plan.