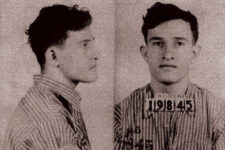

Portrait of cotton mill workers in Georgia, 1909

As the 20th century dawned, the cotton mills of the South were bustling centers of activity, driving the economy yet ensnaring families into a life of hardship and labor-intensive work. The transition from the serene rhythm of farm life to the clamorous environment of the cotton mills was a stark one for the first-generation millhands. They traded autonomy for a life dictated by the relentless pace of machinery, working long hours under someone else’s command for the sole purpose of profit.

In these mills, the concept of family labor was integral, born out of necessity due to the meager wages paid to adult workers. Children, as young as six, were a common sight in these establishments. They were seen as an economical source of labor, capable of performing simpler tasks, contributing to the family income, and adapting quickly to market demands. Between 1880 and 1910, a staggering one-fourth of all cotton mill workers in the South were under sixteen, a testament to the prevalence of child labor during this era.

Life in the mills was harsh and unforgiving. Workers, including children, were introduced to the mill environment at an early age, their lives intricately woven into the fabric of the mill’s demanding schedule. Families were forced to synchronize every aspect of their daily routine, including childcare, to the mill’s unyielding timetable. The mills did not just employ individuals; they consumed entire families, dictating the rhythm of their lives both inside and outside the workplace.

The job hierarchy within the mills was a reflection of the broader societal inequities of the time. Adult white men often occupied the better-paid positions, while women, African Americans, and children filled the lower rungs of the occupational ladder. Notably, African American men were relegated to the most physically demanding tasks, and black women were generally excluded from mill work altogether. The wage structure clearly illustrated these disparities, with children and African American workers receiving the least compensation for their labor.

Despite the meager earnings, the risks associated with working in the mills were immense. Workers faced constant health hazards, such as respiratory diseases from prolonged exposure to cotton dust and the ever-present threat of grievous injuries from the machinery. The lack of insurance or worker’s compensation exacerbated these risks, leaving workers vulnerable in times of sickness or injury.

Nevertheless, amidst the grueling work and harsh conditions, moments of camaraderie and respite could be found. Workers would often socialize, sing, or share stories during breaks or when the machines lay idle. These moments, however fleeting, provided a semblance of relief and a sense of community within the oppressive environment of the mills.

The underlying tensions between the mill owners’ insatiable drive for profit and the workers’ quest for a fair share of the fruits of their labor eventually boiled over. The establishment of the National Union of Textile Workers was a testament to the workers’ desire to assert their rights and improve their working conditions. Although the union struggled to enforce significant change, it marked the beginning of a collective resistance that would continue to grow in the years to come.