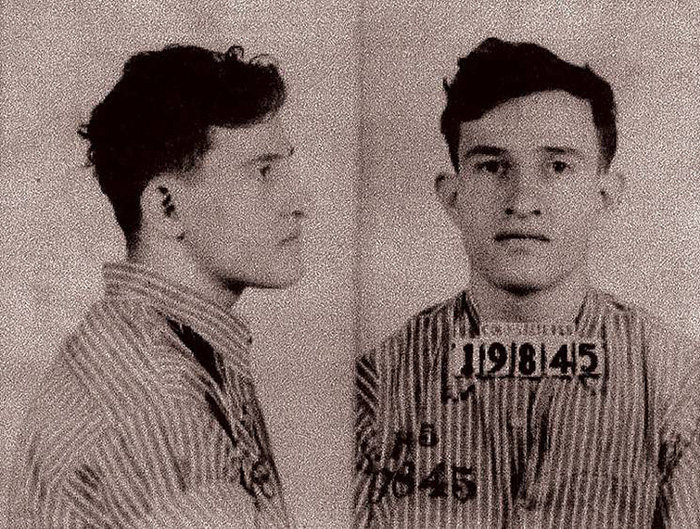

Joe Arridy: The Mentally Disabled Man Executed for a Murder He Never Committed

The tragic story of Joe Arridy, a mentally handicapped young man with an IQ of 46, unfolds as a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities of the intellectually disabled within the criminal justice system. Arridy’s life, marked by suggestibility and innocence, ended in one of the most grievous miscarriages of justice in American history.

The Crime and Coerced Confession

On the night of August 15, 1936, Pueblo, Colorado, was shaken by the brutal murder of 15-year-old Dorothy Drain, found dead in her home, and the assault on her younger sister, Barbara. The frenzied search for the perpetrator led to the arrest of Joe Arridy, who was coerced into confessing to a crime he did not commit. The pressure to solve the case was immense, and the police, under the command of Sheriff George Carroll, exploited Arridy’s intellectual disability to secure a confession, despite the lack of evidence linking him to the crime scene.

The Flawed Trial

Arridy’s trial was a spectacle of injustice. His Syrian heritage and the physical characteristics it imparted made him a target for suspicion in an era of racial prejudice. The fact that his parents were first cousins, contributing to his intellectual disability, was sensationalized by the media, further biasing public opinion against him. Despite clear signs of his vulnerability—his inability to understand basic concepts or defend himself against manipulation—Arridy was convicted and sentenced to death.

The trial ignored substantial evidence of Arridy’s innocence, including the likelihood that the actual murderer was Frank Aguilar, a Mexican man later executed for the crime. The insistence on Arridy’s guilt, even in the face of Aguilar’s conviction, highlights a disturbing willingness to sacrifice the vulnerable to appease public outcry.

The Execution and Its Aftermath

Arridy’s time on death row was marked by a tragic innocence; he spent his days playing with toy trains, a simple pleasure that underscored his childlike understanding of the world. His execution on January 6, 1939, was a somber event, with witnesses noting his obliviousness to the gravity of his situation. Warden Roy Best, who had grown fond of Arridy, was reported to have cried during the execution, a poignant symbol of the humanity that Arridy’s treatment lacked at every other turn.

The posthumous pardon granted by Governor Bill Ritter in 2011, while a symbolic gesture, underscores the irreversible harm inflicted by the justice system on Joe Arridy. It serves as a belated acknowledgment of his innocence and a critique of the death penalty and the treatment of the mentally disabled in legal proceedings.