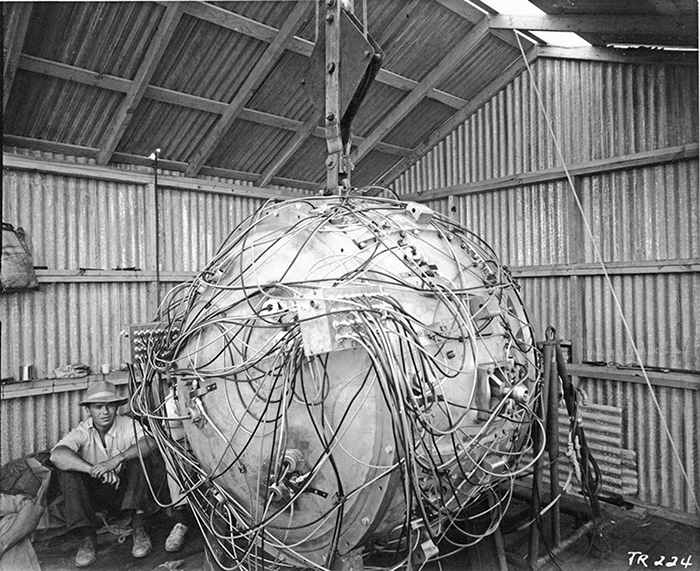

The Gadget, the first atomic bomb, 1945

On a day that would forever change the course of history, the world’s first nuclear weapon detonation, codenamed Trinity, was conducted, marking the dawn of the Atomic Age. The device responsible for this monumental event was affectionately nicknamed “The Gadget” by those who created it. This test, carried out on July 16, 1945, in the desolate desert of New Mexico, was not just a scientific experiment but a demonstration of a new era of warfare and human capability.

The Gadget was an implosion-type plutonium device, mirroring the design of the Fat Man bomb, which would later be used in Nagasaki. This naming convention, a “laboratory euphemism,” reflected a significant milestone in the Manhattan Project, underscoring the moment when theoretical physics met practical engineering. The device was officially cataloged as a Y-1561 device, showcasing the meticulous attention to detail and the high stakes involved in its development.

The engineering behind the Gadget was as fascinating as it was complex. Utilizing an implosion mechanism, the device employed a series of explosives to compress a plutonium core to a supercritical state, initiating a nuclear chain reaction. The intricate setup of these explosives, all burning at different frequencies and meticulously timed, was crucial for achieving the desired implosion symmetry. This precise engineering ensured that the plutonium would be compressed evenly, maximizing the bomb’s yield.

The assembly of this groundbreaking device began in earnest on July 13, 1945, at the McDonald Ranch House, transformed into a makeshift cleanroom for the occasion. The core of the Gadget was assembled with extraordinary care, with the polonium-beryllium initiator placed within the plutonium hemispheres, all encapsulated within a uranium tamper plug. The meticulous assembly process underscored the unprecedented level of precision required for the weapon’s success.

For the test, the Gadget was hoisted atop a 100-foot bomb tower, a testament to the apprehension and ambition that characterized the Trinity test. Among the concerns was the fear, however remote, that the detonation could ignite the Earth’s atmosphere, a catastrophic possibility that was ultimately calculated to be highly unlikely. The device’s yield was estimated to be between zero and 20 kilotons of TNT, with the actual explosion yielding an equivalent of 18 kilotons, creating a massive crater of radioactive glass and a mushroom cloud that stretched 7.5 miles into the sky.

The explosion’s immediate effects were staggering, illuminating the surrounding mountains brighter than daylight and generating heat described as “as hot as an oven” at the base camp. The shockwave from the blast was felt over 100 miles away, a powerful testament to the Gadget’s destructive power.

The Trinity test’s aftermath was a mix of awe and sobering reflection. Kenneth Bainbridge, the test director, and J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director of the Manhattan Project, both expressed profound reactions to the test’s success. Oppenheimer’s recollection of a line from the Bhagavad Gita, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” encapsulated the profound duality of their achievement: the marvel of scientific progress and the ominous reality of its application.

The Trinity test and the Gadget itself stand as pivotal moments in history, symbolizing the immense power of human ingenuity and the solemn responsibility that comes with it. As the progenitor of nuclear weapons, the Gadget opened a Pandora’s box of ethical, political, and military challenges that continue to resonate today.