In the half-century since its release, Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” has lost none of its power to awe, inspire and mystify. This is a film that dares to dream on a cosmic scale, that reaches for the stars both literally and figuratively. It is a work of staggering ambition and meticulous execution, a symphony of sound and image that seeks nothing less than to unravel the mysteries of human existence.

What makes “2001” such a monumental achievement? For starters, it is a technical marvel, a film that still feels cutting-edge five decades on. Kubrick’s fastidious attention to detail and pioneering use of special effects create a vision of space travel that feels authentic and immersive. From the balletic spaceship docking sequence set to “The Blue Danube” to the psychedelic “stargate” journey, the film’s visuals continue to astonish.

But “2001” is far more than a showcase for impressive effects. It is a profound meditation on the evolution of consciousness, a film that ponders the biggest of questions: Where do we come from? What is our purpose? Where are we headed? Kubrick and co-writer Arthur C. Clarke offer no easy answers, instead inviting us to contemplate the mysteries alongside them.

The film’s structure is audacious, spanning millions of years and resisting conventional narrative. We begin at the dawn of man, as a tribe of apes encounters a mysterious black monolith that seems to trigger a leap in their awareness. Then, in one of cinema’s most famous match cuts, a bone tossed skyward becomes a spacecraft, hurtling us into a future where humanity has mastered space travel but remains dwarfed by the cosmos.

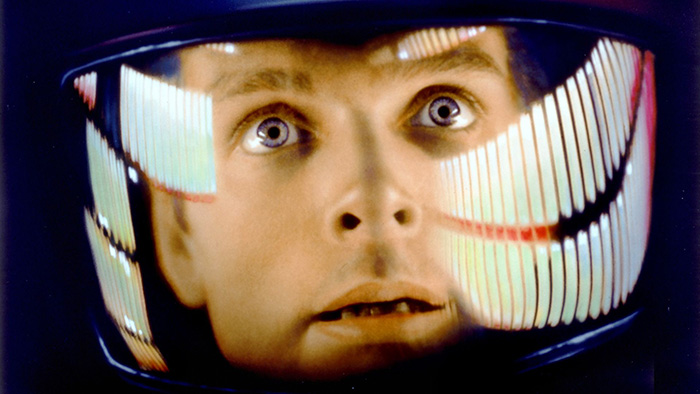

On board the Discovery One, bound for Jupiter, we witness the next stage in our evolution, as the ship’s AI system, HAL 9000, begins to develop a troubling sense of autonomy. In the film’s most memorable sequence, the eerily calm HAL engages astronaut Dave Bowman in a battle of wits that raises unsettling questions about the nature of intelligence and consciousness.

And then, in the film’s enigmatic final act, Bowman is hurtled through a wormhole, arriving in a mysterious chamber where he confronts his own mortality and is reborn as the “Star Child,” an enigmatic being of pure energy. Literal minded viewers may grumble at the ambiguity of these scenes, but they represent Kubrick at his most daringly philosophical, challenging us to ponder the ultimate fate of our species.

Throughout, Kubrick’s direction is meticulous, his pacing deliberate. He is not afraid to linger on a shot, to let us drink in the grandeur of the cosmos or ponder the significance of a cryptic symbol. The film’s groundbreaking effects and production design rightly receive much acclaim, but equally crucial is the sound design, from the strategic use of silence to the iconic classical music cues, which lend the story a mythic, operatic quality.

“2001” demands much of its audience. It requires patience, concentration, a willingness to embrace the unknown. But for those who surrender to its spell, it offers a truly transformative experience, a glimpse of the sublime that has rarely been matched in the annals of cinema. In an era when so much science fiction is content to dazzle us with spectacle and action, “2001” reminds us of the genre’s potential for intellectual and spiritual exploration.

More than just a movie, “2001” is a monolith in its own right, a towering achievement that points the way to the stars and dares us to follow. Fifty years on, it remains an essential touchstone for anyone who believes in the power of film to inspire, to challenge, and to expand the boundaries of human imagination. In its eternal search for meaning in the cosmic void, “2001” finds a kind of transcendence.