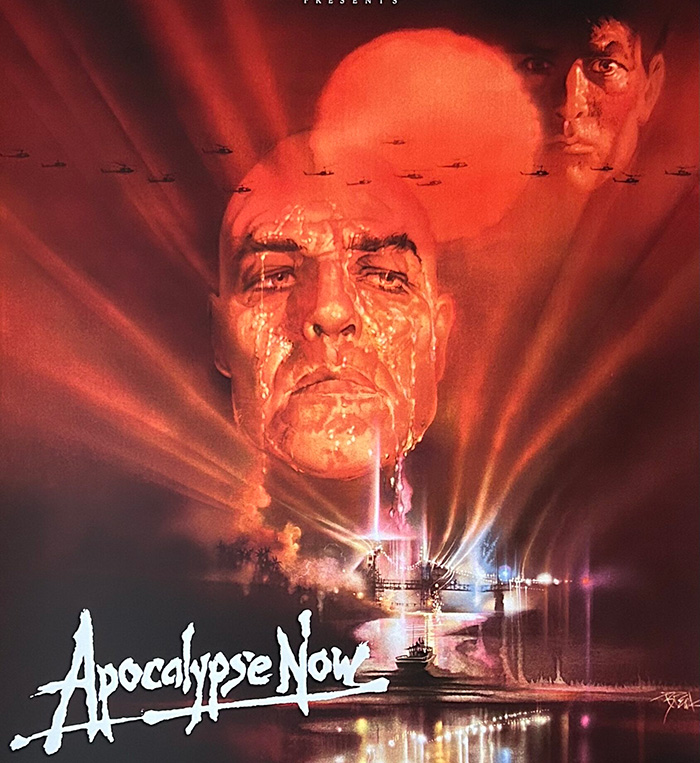

If you ever find yourself watching Apocalypse Now, it’s probably not because you stumbled upon it; it’s because you made a deliberate choice to lose yourself in a film that’s as maddening as it is mesmerizing. Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam epic is not just a film; it’s a fever dream of horror and beauty, a psychedelic reflection of war that aligns more closely with a bad trip than a historical recount.

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola at the height of his ’70s auteur prowess, Apocalypse Now is less a traditional narrative and more a fever dream set to the tune of “The End” by The Doors. It’s a movie that shouldn’t work – the production was notoriously troubled, the script was constantly in flux, and Marlon Brando showed up to set overweight and unprepared. Yet somehow, through sheer force of will and artistic vision, Coppola managed to craft a masterpiece that captures the insanity of war in a way no other film has before or since.

Coppola’s odyssey into the heart of darkness is an exercise in extremes. On one hand, it depicts the surreal horrors of war; on the other, it plunges into the depths of human psyche, crafting a narrative that is as much about the internal battles of its characters as it is about the external chaos. What sets Apocalypse Now apart isn’t just its portrayal of war but how it chooses to portray it—through a lens smeared with madness, with a narrative that feels like it’s coming apart at the seams, mirroring the mental disintegration of its characters.

The film begins with one of the most iconic opening sequences in cinema history—a hotel room in Saigon, ceiling fans morphing into helicopter blades, The Doors’ “The End” playing as napalm burns in the distance. This sequence alone encapsulates the film’s overarching theme: the fine line between reality and insanity.

Captain Willard, played with a haunting intensity by Martin Sheen, is tasked with assassinating Colonel Kurtz, a rogue military officer who has set himself up as a god among a local tribe deep in the Cambodian jungle. The mission is clear, but the journey is anything but. It’s a descent into hell, a trip down a river that might as well be Styx, each stop deeper into the jungle revealing more about the war and human nature than most would care to admit.

Let’s talk about the river. It’s like the third act of every Greek tragedy you half-remember from college; it serves as a metaphor for the journey into the subconscious. Every stop Willard and his PBR crew make is a further descent into the madness of war, and each encounter is more bizarre and unsettling than the last. You’ve got the hyper-militarized, surf-crazy Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore, who drops napalm on a Vietnamese village just to catch some good waves. The man’s philosophy—“I love the smell of napalm in the morning”—might as well be the tagline for the absurdity of military escalation.

But as Willard travels deeper into the jungle and further from conventional morality, the film transforms. It’s less about the physical journey and more about the unraveling of his sanity, reflecting the madness that Kurtz has succumbed to. The deeper Willard goes into the jungle, the more he isolates from what you or I might call “reality.” This river isn’t just a route on a map; it’s a liquid flowchart that tracks the slow disintegration of rational thought, showing us that the line between sane and insane is as thin as a riverbank on this murky waterway.

When Willard finally meets Kurtz, the film shifts from a war movie into a dark, existential dialogue between two lost souls on opposite ends of the same psychological collapse.

Marlon Brando’s Colonel Kurtz is the dark soul of the film, a man who has seen the horrors of war and has been transformed by them into something both terrifying and tragic. His performance is less about the physical presence and more about the aura of a man who has gone beyond the edge. Kurtz is not just a character; he’s a mirror reflecting the darkest parts of the soul, the parts that war exposes and expands.

His monologues are dense, almost inscrutable, but they hit you with the force of a sledgehammer. This isn’t just dialogue; it’s a manifesto of madness. Kurtz is not just a man; he’s an ideology, the personification of the heart of darkness that Joseph Conrad wrote about. He’s what happens when a man looks so long into the abyss that he becomes the abyss.

The finale, a frenzied sacrificial ritual intercut with Willard’s assassination of Kurtz, is pure cinematic alchemy. You’re not just watching a climax; you’re experiencing a catharsis. It’s like the entire film has been building pressure, and here it finally blows. The horror, the horror—it’s not just Kurtz’s realization; it’s ours.

Apocalypse Now is not a film that allows you to remain a passive viewer. It demands your engagement, challenges your perception of heroism and morality, and leaves you with images and questions that linger long after the credits roll. It’s a film that doesn’t just depict a journey—it is a journey, one that pushes you into the uncomfortable depths of human nature and leaves you there to find your way back.

In the end, Apocalypse Now isn’t just about the horrors of the Vietnam War. It’s about the horrors within us all, the darkness that lurks beneath the surface, waiting for the chaos of war to set it free. It’s a masterpiece not because it provides answers, but because it dares to ask questions—questions about war, about civilization, about sanity and madness. It’s a film that, like the river it follows, sweeps you into the heart of darkness and doesn’t promise to bring you back. It’s not just a movie; it’s an experience—a haunting, beautifully horrific experience that redefines what a war film can be.